What is uveitis?

Uveitis is the inflammation of the uvea. When any part of your uveal tract is inflamed, then you have uveitis, or least a form of it.

So what exactly is the uvea?

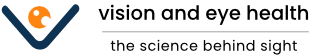

The uvea can be considered as the middle layer of the eye. It consists of the iris, ciliary body and choroid.

Diagram showing the anatomy of the eyeball. The uvea comprises the iris, ciliary body and choroid – these are highlighted in red boxes. Note the attachment of the lens to the ciliary body via the zonules. Also note the location of the choroid between the sclera and retina.

The iris is the colored part of the eye that surrounds the pupil. The iris muscles control pupil size and hence the amount of light that enters the eye. The ciliary body connects the iris and choroid. It produces aqueous (natural fluid in the eye) and provides an attachment for the zonules of the lens. The choroid sits in between the sclera (the tough outermost coat of the eyeball) and the retina (the innermost lining of the eyeball which receives light and converts it to biochemical signals). The choroid is rich in blood vessels and supplies the retinal cells with nutrients. The uvea is therefore a very important part of the structure of the eye.

There are many different types of uveitis, and so how it affects you may not be how it affects other people. Some forms, such as iritis, cause pain and light sensitivity. Other forms, such as chorioretinitis, cause visual loss and floaters. So while it can be somewhat confusing, do remember that uveitis is an umbrella term for a spectrum of different inflammatory conditions affecting one or more parts of the uvea.

What are the different types of uveitis?

Based on the anatomical location of the uveal inflammation, uveitis can be broadly classified into 3 groups:

Anterior uveitis: This is the inflammation of the front tissues of the uvea, namely the iris and ciliary body. Inflammation of the iris is called iritis. If the inflammation also affects the ciliary body, this is called iridocyclitis. It is the most common form of uveal inflammation. Fortunately, it is also readily treated with steroid eye drops.

The picture on the left shows a classic sign of longstanding iritis – an irregular pupil due to adhesions of the iris to the lens surface (posterior synechie). The picture on the right shows a hypopyon in severe iritis.

So what happens when you get iritis or iridocyclitis? The common symptoms are eye pain, tenderness on touching and light sensitivity (photophobia). Photophobia occurs because light worses the spasm of the iris muscles caused by the inflammation. The area encircling the iris will look inflamed. If severe and/or longstanding, your pupil may become misshapen and part of it stuck to your lens (posterior synechie). There may also be a yellow fluid level in the eye due to accumulation of inflammatory and pus cells – this is known as a hypopyon. Complications of untreated iritis include cataract and glaucoma.

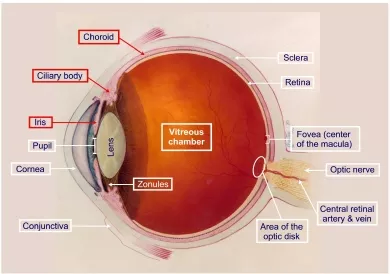

Intermediate uveitis: This is the inflammation of the middle part of the uvea, namely the pars plana or area between the ciliary body and retina. This condition is also called pars planitis. It is the next commonest form of uveal inflammation.

With pars planitis, you will notice floaters. Occasionally, there may be pain and photophobia. If severe, you may experience blurred vision due to cystoid macular edema. The typical signs are “snowballs” and “snowbanking”, which can only be seen clinically through a fully dilated pupil.

The picture on the left demonstrates the location of the pars plana. The illustration on the right graphically shows the clinical features of pars planitis – snowballs, snowbanks and cystoid macular edema.

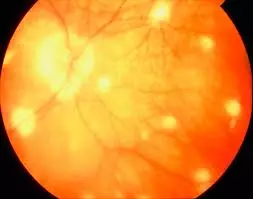

Posterior uveitis: This is the inflammation of the choroid. Due to the proximity of the choroid to the retina, the retina is also commonly affected. This condition is commonly called choroiditis or chorioretinitis if the retina is involved.

Chorioretinitis causes visual loss through inflammation of the choroid and retina. Depending on the severity, it can also cause vitritis (inflammation of the vitreous), cystoid macular edema (swelling of the macula) and optic neuropathy (damage to the optic nerve), all of which also affect the vision. Chorioretinitis can be a difficult condition to treat and may require long term treatment with oral steroid or immunosuppresant medication.

Chorioretinitis is seen clinically as yellow white spots at the back of the eye. The term chorioretinitis encompasses a wide range of clinical conditions. Chorioretinitis caused by infection include toxoplasma chorioretinitis and HIV chorioretinitis. Non-infective entities include birdshot chorioretinopathy, serpiginous chorioretinitis and sarcoidosis.

How can uveitis be managed?

Inflammation of the uveal tract can be quite difficult to diagnose and treat. This is due to the many causes of such inflammation – trauma, infection or autoimmune, when your body recognises a part of your eye as being foreign.

In addition, it may be a purely isolated eye problem or may be associated with a general medical condition such as syphilis or HIV. Although the disease can generally be controlled, a complete cure is usually not achieved. There are some prevention measures that may help you to reduce your risk of developing uveitis.

If your inflammation is recurrent or occurs in both eyes, you will need to undergo various uveitis investigations including blood tests and X-rays to discover the cause of the inflammation. To ascertain the severity of the inflammation, you may also need to undergo eye-related tests such as OCT scanning and fluorescein angiography. The results of these investigations will help to establish the correct diagnosis and determine the best treatment options.

The aims of treatment are to:

1. Provide symptomatic relief from any pain

2. Prevent or reduce visual loss from the inflammation

3. Prevent or reduce any associated complications

4. Treat the underlying cause of the disease

The main treatment for uveitis is corticosteroids (or steroids for short). Steroids can be administered in various ways, either as eye drops, intravitreal injections, periocular injections, tablets or intravenous infusions, depending on the suitability for the different types of inflammation. If steroid therapy is unable to control the inflammation sufficiently, additional immunosuppresant medication. Usage of these medications require specialist supervision and close follow-up due to the risks of immune suppression, kidney damage and liver damage.

Intraocular surgery may also be necessary for the treatment of any associated complications. These include vitrectomy to clear the vitreous cavity of inflammatory debris, glaucoma surgery to lower the intraocular pressure and cataract surgery. Due to the relatively high incidence of associated complications, regular follow-up and monitoring is essential so that any problems can be picked up early and dealt with accordingly.